Of The 1940s

Mere years after the introduction of sound technology into film, Hollywood would nearly nose dive in 1941 and then reach the heights of its most profitable year in the 40s in 1946. These years are telling for the casual historian. 1941 saw the destruction of Hollywood’s foreign markets due to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7 and this would officially mark the end of America’s isolationist policies and their entrance into the world stage of World War II. The world would see the demise of one of history’s most notorious dictators during a brutal war that would cost millions of lives between all of the nations involved in the war effort. The war would end on Sept. 2, 1945. It makes sense then that 1946 in the aftermath of a second “war to end all wars” that the general trend would be towards enjoying the luxuries that were not present during wartime. Hollywood films finally came into vogue and were a modern form of entertainment, not just the novelty items of curio shops.

Mere years after the introduction of sound technology into film, Hollywood would nearly nose dive in 1941 and then reach the heights of its most profitable year in the 40s in 1946. These years are telling for the casual historian. 1941 saw the destruction of Hollywood’s foreign markets due to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7 and this would officially mark the end of America’s isolationist policies and their entrance into the world stage of World War II. The world would see the demise of one of history’s most notorious dictators during a brutal war that would cost millions of lives between all of the nations involved in the war effort. The war would end on Sept. 2, 1945. It makes sense then that 1946 in the aftermath of a second “war to end all wars” that the general trend would be towards enjoying the luxuries that were not present during wartime. Hollywood films finally came into vogue and were a modern form of entertainment, not just the novelty items of curio shops.

During the war years, however, there was an intentional drive within Hollywood towards helping with the national propaganda through newsreels, short films, war films, etc. to update their audiences on what was going on, globally, around them. The setup of the Office of War Information in 1942 would see the official bureaucratic tie between the US government and the Hollywood industry. Looking at this period of Hollywood history is fascinating because most people alive now have an opposite understanding of the relationship between Hollywood and the US government. The Korean War would mark the final conflict in which there was little to no animosity between the two. That would be jumping ahead of where we are now however. At this time, Hollywood pushed all of its stars to enlist and go overseas to fight in the war. People who would become some of the greats of American cinema fought in WWII like Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart and director Frank Capra.

This time saw the rise of some of the greatest directors as well. John Huston, John Ford, Capra and William Wyler would start their careers with wartime documentaries and training films. Also, a new wave of movie stars that would make Hollywood film and celebrity much more attractive to the general populace. The rise of Betty Grable and Rita Hayworth would begin the trend of Hollywood starlets. Since the curiosity of moving images had become common to most at this point, film had to come into maturity in technological and narrative forms. Developments toward sound, lighting, color, cinematography and other key elements of film making would modernize the art moving it from sideshow attraction to the art that it would become.

Through the near death and rebirth of the industry, we see that this period was particularly important to not only the economic, but the cultural development of the cinema in American society. That near death created the crux by which key movers in the industry would learn how to push through external factors out of their control in order to keep the art form alive. There was a significant shift in the type of movies presented as well. During the Great Depression in the 30s (like we talked about last month), there was a need for escape from the domestic economic problems that laid over the whole land. With the WWII, Hollywood began to get serious and the films created took on a more realistic (perhaps naturalistic) tone.

Through the near death and rebirth of the industry, we see that this period was particularly important to not only the economic, but the cultural development of the cinema in American society. That near death created the crux by which key movers in the industry would learn how to push through external factors out of their control in order to keep the art form alive. There was a significant shift in the type of movies presented as well. During the Great Depression in the 30s (like we talked about last month), there was a need for escape from the domestic economic problems that laid over the whole land. With the WWII, Hollywood began to get serious and the films created took on a more realistic (perhaps naturalistic) tone.

War films and documentaries tried to get as close to the perception of soldiers and war while some of the horror of the time became more suggestive instead of showing the monster like Universal did in the 1930s. Val Lewton’s productions like Cat People and Body Snatcher would find their terror in what was not shown, but in the implication of those things hidden or in the shadows. This makes sense considering WWII created a marr in the armor of Western nations who truly thought WWI would be the end of war as they knew it. Now, there was a lack of certainty about what was around the corner and what the next threat might be. In this way horror adapted to the changing circumstances of the world. We have seen the monsters, what could possibly be worse? The things lurking in the shadows could be and horror began to exploit the psyches of its audiences in the wake of the fragile period of American history.

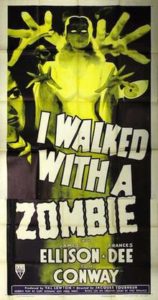

Val Lewton teamed up with Jacques Tourneur once again a year after the release of Cat People for a new tale entitled I Walked with a Zombie about a Canadian nurse, Betsy, who goes to the West Indies to care for the wife of a plantation owner who seems to be…well, a zombie–of the voodoo variety which was standard before Night of the Living Dead. Betsy finds herself in the midst of an already-feuding family which sets up the tension and mystery of the film’s central premise: what is wrong with Jessica and did her husband play a part in it?

Val Lewton teamed up with Jacques Tourneur once again a year after the release of Cat People for a new tale entitled I Walked with a Zombie about a Canadian nurse, Betsy, who goes to the West Indies to care for the wife of a plantation owner who seems to be…well, a zombie–of the voodoo variety which was standard before Night of the Living Dead. Betsy finds herself in the midst of an already-feuding family which sets up the tension and mystery of the film’s central premise: what is wrong with Jessica and did her husband play a part in it?

As was often the case in early American horror, the film traded in exoticizing–read: exploiting–the perceived superstitions and culture of the black populace in the West Indies. Betsy hears from her black chauffeur about how the Hollands (the family of the plantation owner) brought slaves to the island. Slavery and colonialism provide the background for the film as we, the audience, attend to the mystery at its heart. Is Holland’s wife under his control, the control of the natives or is she just sick in accordance with Western medical practice.

We come to find out that the matriarch of the family is behind Jessica’s sickness. Holland’s brother was going to run away with Jessica so Mrs. Rand placed her under a voodoo spell so the family would not be broken apart. Mrs. Rand used voodoo in order to manipulate the natives towards Western medical practices instead of “superstition.” However, when her youngest son was about to run away with her oldest son’s wife, she became possessed by a voodoo god and then placed the curse on Jessica.

Mrs. Rand’s actions in this film and the decay of her family is significantly tied–more than likely, unconsciously–to the legacy of slavery and colonialism and the justifications of those systems by way of Enlightenment rationalism and materialism. The fact that Mrs. Rand appropriates the religious practices of the native peoples in order to manipulate them towards that which the West deems more cultured, intelligent, and “scientific” says much about how colonialism controls those who are conquered and ultimately decays the moral fabric of those who control. The decay of the family ties in the film have a direct link to the slavery and colonial heritage that underpins the family’s very status on the island.

Mrs. Rand’s actions in this film and the decay of her family is significantly tied–more than likely, unconsciously–to the legacy of slavery and colonialism and the justifications of those systems by way of Enlightenment rationalism and materialism. The fact that Mrs. Rand appropriates the religious practices of the native peoples in order to manipulate them towards that which the West deems more cultured, intelligent, and “scientific” says much about how colonialism controls those who are conquered and ultimately decays the moral fabric of those who control. The decay of the family ties in the film have a direct link to the slavery and colonial heritage that underpins the family’s very status on the island.

By placing Jessica under the curse of voodoo magic, she places her into a power that she doesn’t actually understand, but only tries to wield for her own benefit. Yet the things she achieves by wielding that power come at a price which only the native peoples understand. She ends up destroying her youngest and the wife of her oldest. Colonial power was (still is) wielded by imperial powers and soon there would come a cost. One could make a case that the wars of the 20th century have their origin in the land grab and greedy, careless grappling for power that many first world countries partook in leading up to the 20th century. Those wars were the cost, just like the death of Rand’s son and disintegration of her family was her immediate cost for the sins of her family.

I Walked with a Zombie then becomes a cautionary tale about the generational curse that can be bestowed on those who seek to control and enslave their fellow man and woman and children in order to ascertain money and power. They may get away with it for quite awhile, but the cost will be paid at some point. In this way, the film could easily be seen as a fitting allegory for the state of the world during the 1940s and on into the following decades with continuing global conflicts. After all, absolute power corrupts absolutely. Wait, scratch that, all power, if left unchecked, can corrupt us. It’s just the harvest we reap from it varies in its time.

I Walked with a Zombie then becomes a cautionary tale about the generational curse that can be bestowed on those who seek to control and enslave their fellow man and woman and children in order to ascertain money and power. They may get away with it for quite awhile, but the cost will be paid at some point. In this way, the film could easily be seen as a fitting allegory for the state of the world during the 1940s and on into the following decades with continuing global conflicts. After all, absolute power corrupts absolutely. Wait, scratch that, all power, if left unchecked, can corrupt us. It’s just the harvest we reap from it varies in its time.