Oh! The Horror… | of the Coming

“O come, O come, Emmanuel,

And ransom captive Israel,

That mourns in lonely exile here,

Until the Son of God appear.

Rejoice! Rejoice! Emmanuel

Shall come to thee, O Israel.”

Advent has passed, as has the celebratory birth date of Christ, but it is never too late to marvel at the strangeness of the church’s annual practice of waiting for the coming condescension—God become man. Every year, the church—except for those stuffy sectors that find the Church calendar to be an actual affront—commemorates the anticipation surrounding the savior of the world, the opening act of the divine mystery. An all-powerful, all-knowing, all-good Creator humbling Himself in the body of fragile human flesh in order to fulfill and clarify the Law given to the Jews and then die for the sins of the world by having the human flesh torn from his very skeleton. God puts on skin and then His hide gets skinned; another mocking by the devil himself. It is the source of humanity’s only salvation, so the good book reads.

Advent has passed, as has the celebratory birth date of Christ, but it is never too late to marvel at the strangeness of the church’s annual practice of waiting for the coming condescension—God become man. Every year, the church—except for those stuffy sectors that find the Church calendar to be an actual affront—commemorates the anticipation surrounding the savior of the world, the opening act of the divine mystery. An all-powerful, all-knowing, all-good Creator humbling Himself in the body of fragile human flesh in order to fulfill and clarify the Law given to the Jews and then die for the sins of the world by having the human flesh torn from his very skeleton. God puts on skin and then His hide gets skinned; another mocking by the devil himself. It is the source of humanity’s only salvation, so the good book reads.

This coming of something vague and abstract in the minds of the Hebrews at the time was often interpreted as something other than what actually came. Something more akin to the good book’s imagery of Christ’s second coming. A king who deposes the powers of the world and reigns with his people free. They didn’t expect earthly freedom being only part of the bargain. Christ came to free the body and the soul, the heavens and the earth made new. Spiritual and earthly concerns were in view. When Christ’s first tinny cry pierced the air amidst the animal dung and urine, no one expected that God would come in utter weakness and vulnerability. Yet He came in complete humility.

The expectations inherent in anticipation are often mere shadows of the thing that actually arrives. In this, Advent and horror have much in common. Horror thrives on going against the haughty reason and expectations of humanity. Sure, that Hasbro Ouija board is a mere game to be laughed at and enjoyed. What comes from it is wholly other and without precedent in the lives of those who are projected upon the silver screen. Oh yeah, the Native American burial ground is ripe for housing developments! It’s only dirt and root. What comes is not only profit, but blood screaming forth from the ground like Abel. Humanity’s reason and expectation is too earthly and doesn’t allow the room for mystery and consequences that transcend our progressively perfected understanding of reality. Horror gives viewers the unexplained as a response to their explanations.

There is horror cinema and literature that thrives on destroying the expectations on all sides of the human spectrum. A couple of recent examples are The Mist and 10 Cloverfield Lane. Both of these films trade on the idea that what is outside the doors not only defies human understanding and rationality, but shows that some of the characters have imaginations that come closer to the actual reality than others. While they, too, ultimately get it wrong, it is their willingness to find a narrative that moves beyond the materialism of enlightened man which gets them nearer the truth than the other characters. They are looked at with a side-eye or absolute derision for not following the flow of collective human reasoning. These prophets of doom falter by basing their understanding solely on fear. Fear is ultimately self-defeating, yet has a way of releasing the mind to dig deeper into mystery and grander conspiracy.

There is horror cinema and literature that thrives on destroying the expectations on all sides of the human spectrum. A couple of recent examples are The Mist and 10 Cloverfield Lane. Both of these films trade on the idea that what is outside the doors not only defies human understanding and rationality, but shows that some of the characters have imaginations that come closer to the actual reality than others. While they, too, ultimately get it wrong, it is their willingness to find a narrative that moves beyond the materialism of enlightened man which gets them nearer the truth than the other characters. They are looked at with a side-eye or absolute derision for not following the flow of collective human reasoning. These prophets of doom falter by basing their understanding solely on fear. Fear is ultimately self-defeating, yet has a way of releasing the mind to dig deeper into mystery and grander conspiracy.

Human expectations are often smaller than what they could be and that is because we box ourselves into a framework that has only really been primary for hundreds of years. Philosophers and theologians in ancient days would often find themselves enraptured by minutiae. This form of speculation allowed for mystery and human enquiry to combine. Very few things were taken for granted. Assumptions were consistently challenged. Expectations were malleable. When flawed humans become the central authority, blindsiding happens all the time. A God-man enters the world unbeknownst to even the leading scholars on who the Messiah was supposed to be. When God becomes the center, exploration, curiosity and imagination become concentric circles moving inward and outward, endlessly.

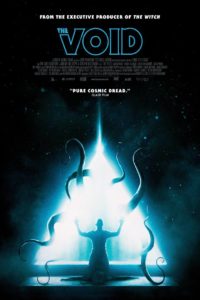

Certain writers during the Enlightenment would push back at times against this solidified wall of “scientific rationality.” H.P. Lovecraft–one such author–was in tune with this depletion. He, like many in the Enlightenment, assumed human reason was at the center of all knowledge and understanding, yet he understood its limits. We look out beyond what can be sensed and we see darkness, the void. God releases the creatures from the deep that inhabit the orbits of our solar system without giving safety from their revelation. Lovecraft knew the inherent fear in treading along the boundaries of assumptions about how humans try to conquer reality by way of their mind. It never reveals anything good, only the coming of madness.

The revelation of Scripture in the Gospels, then, becomes a balm to the terrified and wearied human soul. It contextualizes humanity and surrounds them with their Creator’s presence so when they look inward and outward, there is room for exploration, scientific discovery and existential truth and, yet, it points towards the true center of the orbit: the Son. The creatures from the deep are still present, but there is a safe harbor in which we can gather. They cannot do anything to thwart God. Their revelation pales against his salvific plan for save us—the Divine sacrifice.

The revelation of Scripture in the Gospels, then, becomes a balm to the terrified and wearied human soul. It contextualizes humanity and surrounds them with their Creator’s presence so when they look inward and outward, there is room for exploration, scientific discovery and existential truth and, yet, it points towards the true center of the orbit: the Son. The creatures from the deep are still present, but there is a safe harbor in which we can gather. They cannot do anything to thwart God. Their revelation pales against his salvific plan for save us—the Divine sacrifice.

Horror is the advent of our own making: the creatures, the ghosts, the slashers, the cannibals and the zombies revealing themselves to us as a negation of our idolatrous worship of rationality. Whereas the advent of Christ seeks to de-fang the horrors of the void and shred its curtain allowing the Son’s light to illuminate the darkness.