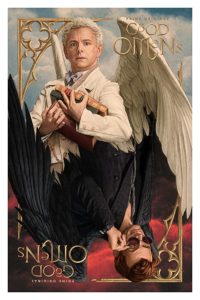

Good Omens‘ Ineffable Apocalypse

It’s difficult, bordering on impossible, to talk about Amazon & BBC’s Good Omens miniseries from a Christian perspective without talking about the Biblical setting it inhabits and the Christian trappings it wears.

It’s difficult, bordering on impossible, to talk about Amazon & BBC’s Good Omens miniseries from a Christian perspective without talking about the Biblical setting it inhabits and the Christian trappings it wears.

Many are obvious, like the angelic and demonic leads, the end-of-the-world setting, and the four horsemen; less self-evident are Adam being tasked with naming an animal, just like the Adam of Genesis, or the name of the witch Anathema meaning “cursed and ostracized.”

One of the most important and repeated references, though, is to the “ineffable” plan of God. Aziraphale explains it in the first five minutes of the show: God’s grand plan, he says, is ineffable.

Crowley: “The Great Plan’s ‘ineffable?'”

Aziraphale: “Exactly. It is beyond understanding, and incapable of being put into words.”

Not only is it impossible to understand, Aziraphale insists, it’s not even for us to understand. Even if we could, we shouldn’t. “Best not to speculate.”

Not only is it impossible to understand, Aziraphale insists, it’s not even for us to understand. Even if we could, we shouldn’t. “Best not to speculate.”

This, as the angel and demon standing upon the walls of Eden are about to discover over the next six thousand years, is not precisely what we would call “true.”

Spoiler alert: plot and ending spoilers follow for Good Omens. And they’re some world-ending spoilers, too.

God at a Distance

To know God’s plan first requires knowing God. The history and tradition of the Western church, particularly as told by those with more grounding in Church than in Christ, paints a picture of God as an inscrutable, unknowable, aloof being. A famous hymn by William Cowper assures us that “God moves in a mysterious way, His wonders to perform”—a sentiment so popular it even made it into the English lexicon.

But even the most fervent study of Scripture will not reveal an unknowable God. One might ask how I could know this, to which I would reply quite simply: why would a God who does not wish us to know Him write a Bible to us?

And in that Bible, far from being a book of abstruse and distant prophecies, God explicitly says He will (and wants to) be known: “You will seek me and find me, when you seek me with all your heart…[My people] shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, declares the LORD,” in the book of Jeremiah. His prophet Hosea implores us, “Let us know; let us press on to know the LORD.” He even instructs Paul to make tough concepts simple by “speaking in human terms, because of your natural limitations” in the book of Romans.

And in that Bible, far from being a book of abstruse and distant prophecies, God explicitly says He will (and wants to) be known: “You will seek me and find me, when you seek me with all your heart…[My people] shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, declares the LORD,” in the book of Jeremiah. His prophet Hosea implores us, “Let us know; let us press on to know the LORD.” He even instructs Paul to make tough concepts simple by “speaking in human terms, because of your natural limitations” in the book of Romans.

And, of course, the ultimate proof that God never intended to be ineffable: He sent Jesus to Earth, to know and to be known.

This is not to say that there will not be mysterious things about God. Of course there are, because we are finite beings and cannot hold an infinite God in the three pounds of synapses atop our bodies. But the Bible’s words, stories, central Hero, even its very existence speak of a God who wants to be known by His people.

God can be known. And His plan can be known. The “Ineffable Plan”…isn’t!

God’s Ineffable Plan

In fact, God’s plan is very much based on God’s nature. He is just and merciful; and so the prophet Micah tells the people, “He has told you, O man, what is good; and what does the LORD require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?”

At the climax of the series, when Gabriel and Beelzebub are trying to convince Adam to live up to his nature as the spawn of Satan, it all comes down to the Archangel confronting the Antichrist. “Well, you can’t just refuse to be who you are,” Gabriel tells him. “Your birth, your destiny, they’re part of the Great Plan.”

At the climax of the series, when Gabriel and Beelzebub are trying to convince Adam to live up to his nature as the spawn of Satan, it all comes down to the Archangel confronting the Antichrist. “Well, you can’t just refuse to be who you are,” Gabriel tells him. “Your birth, your destiny, they’re part of the Great Plan.”

“Is that the Ineffable Plan?” Aziraphale asks. Beelzebub and Gabriel are nonplussed, but Crowley gets it: if the plan is ineffable, and only God knows it, then angels and demons don’t. They’re making it up! They’ve come up with a way to have a war they both want, and humans must pay the price; but it’s not God’s Ineffable Plan.

Because there isn’t an Ineffable God, so there isn’t an Ineffable Plan.

Still, a part of what Gabriel says is true: God’s plan is not as much about what we do, but who we are. Following God’s plan means not refusing to be who we are. Theologian Jen Wilkin says in her series on the book of James,

“What I have to ask is, why are we all still wandering around trying to find the will of God in our lives? Why are we still looking for something that the Lord has faithfully proclaimed to us in His word? And I think it’s because we think that the will of God is something that we should do, instead of someone who we should be! Because what does Scripture say? You are to be saved, to be filled with the Spirit, to be sanctified, to be submissive, to be a sufferer, to be obedient! Do you understand that if we were to be the person that the Lord has willed that we would be, then our doing would fall in line because of our being? So we can stop looking for the secret decoder ring that will tell us what is the right thing to choose, because the Lord has already clearly told us, ‘this is the will of God for your life.'”

—Jen Wilkin

The Will of God, the Great Plan, isn’t ineffable. God desires us to seek Him and made us to know Him. And all the Revelation-shaped story elements in Good Omens are a testament to the way God made for us to know Him: through the Bible.

Yet for all the ways that Aziraphale and Crowley’s story lives and works in the Biblical apocalypse, there’s one pretty major way it differs from God’s story.

Namely, that God isn’t there.

God-Free Apocalypse

Good Omens‘ narrator offhandedly identifies herself as God at the start of the show; but aside from a brief vocal interaction with Aziraphale over the subject of a misplaced sword, we don’t see anyone actually talk to the Almighty during the entire runtime of the series. We see signs of a higher power, of course, and those in the know all speak as though the Lord’s reign is as much a foregone conclusion as the sunrise. Still, in a story about the end times, the absence of the God who leads the throngs of heaven is striking.

Without God, things are slightly…off. The halls of heaven are expansive and utterly empty, even when populated by a regiment of battle-ready angels. The rooms are clinical and dreadfully dull. Even the grand audience chamber where Gabriel and his fake-smiling cadre consult about the upcoming war (and attempt to assassinate Aziraphale when he cancels it) is merely a blank, dull, empty, boring room. The Bible says that the entire temple of God is filled with His intimacy, His glory—and without God, it seems that nothing is left but a voided shell.

Without God, things are slightly…off. The halls of heaven are expansive and utterly empty, even when populated by a regiment of battle-ready angels. The rooms are clinical and dreadfully dull. Even the grand audience chamber where Gabriel and his fake-smiling cadre consult about the upcoming war (and attempt to assassinate Aziraphale when he cancels it) is merely a blank, dull, empty, boring room. The Bible says that the entire temple of God is filled with His intimacy, His glory—and without God, it seems that nothing is left but a voided shell.

This leaves behind, quite frankly, the heaven that culture tells us awaits. Lifeless, lackluster, lonely, lame. The remarkable sights of Isaiah 6 are gone, because God is gone. Heaven is nothing without God being there.

And heaven is just the beginning. Without God, the battle between Heaven and Hell really is a toss-up; and since the pharisaical angels of the story aren’t guaranteed a win, they resort to devious, devilish tricks to bring about the victory, and even the war they need to attain it. While angels in the Bible preach peace and the coming of the Lord, angels of Good Omens are distinctly more violent.

Their leader changes perhaps the most in a world devoid of the Almighty. Without God, even Gabriel becomes a villain, seeking to marshal an army against Hell and needing the war of the end of days as an excuse to do so. Eager to prove how good he is, to show the embers of the world how righteous and powerful he’s become. It’s no longer God’s Ineffable Plan he’s following, but a “Great Plan” seemingly of his own devising. For his own glory, he’s driven even unto murder. He’s fallen into the same sin that caused the demons to fall in the first place: putting himself in the place of God.

It’s not so surprising. Absent God, we all tend toward our own purposes; to the point of destroying the world, if we have the power (and the angels do). Gabriel is remarkably human in this way.

And indeed, without God, the best anyone can be is human. Crowley and Aziraphale prove it, when their humanity inspires them to save the world instead of allowing Heaven and Hell to lay waste to it. Humanity saves Adam from being the Antichrist. And humanity defeats the Four Horsemen (or three of them, at least).

But humans also created the infirmities that give the Four Horsemen power. Our weak, pitiful spark of goodness so often smothers beneath the weight of the sin we hold so dear. And even the end of Good Omens holds little hope for our long-term future; though apocalypse was averted today, it suggests, a final battle between Earth and the combined powers of Heaven and Hell awaits.

Though there is no alliance between the true Heaven and Hell, our helplessness is the same. Our only way out is the return of God.

And in our world, the good news is that He never left.

• • •

Special thanks to my wife Natalie for her help with this one.