The Binding and Loosing of Mickey Mouse

The Walt Disney Company‘s long road to becoming one of the most powerful, celebrated, and litigious entertainment companies on Earth actually began, not with a mouse, but with a rabbit.

The Walt Disney Company‘s long road to becoming one of the most powerful, celebrated, and litigious entertainment companies on Earth actually began, not with a mouse, but with a rabbit.

Inspired by the personality of silent film luminary Douglas Fairbanks and the comedy sensibilities of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, and selected to be a rabbit because there were too many cats in cartoons, Walt Disney and animator Ub Iwerks created Oswald the Lucky Rabbit in 1927 to fulfill a 26-film deal with Universal Studios. That rabbit was a runaway hit for Universal; but over the course of the next year the relationship between Universal and the fledgling Disney began to sour until it broke entirely.

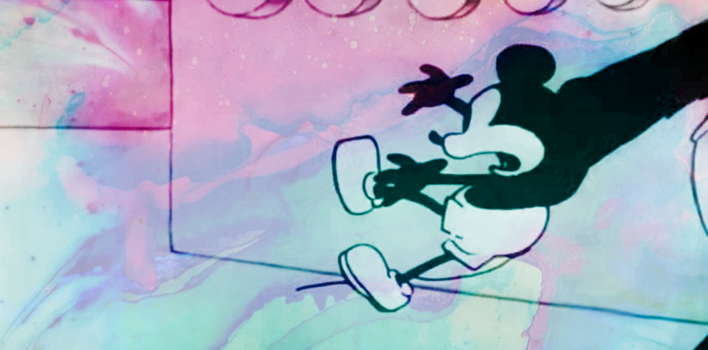

Since Universal owned the rights to Oswald, Disney was stuck, at least legally: his most popular character belonged to someone else, meaning that if he wanted to do anything in animation, he‘d need some different ideas. Those ideas became, after a train ride and a name suggestion by his wife, an animated mouse named Mickey; and the mouse‘s wide debut in 1928‘s Steamboat Willie made both Mickey and Disney international stars.

Yes, this is legal!

But even as he began construction on his own legacy, Walt was building on works that weren‘t owned by anyone. Steamboat Willie was the first popular cartoon with a synchronized soundtrack, and one of the songs included was “Turkey in the Straw;” which had gone into the public domain around eighty years prior. The next two shorts, The Gallopin‘ Gaucho and Plane Crazy, featured “Kingdom Coming” and “Goodnight Ladies,” two Civil War-era songs whose copyrights had only just recently expired, putting them into the public domain as well.

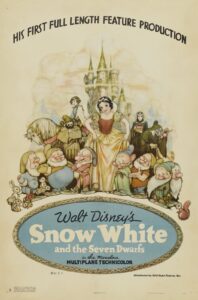

And that was just the start of Disney‘s long love story with non-copyrighted material. Beginning with their very first feature in 1937, The Walt Disney Company adapted the stories of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, Pinocchio, The Sorcerer‘s Apprentice in Fantasia, Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Sleeping Beauty, Robin Hood, and many more from the public domain as it grew into the paragon of animated fantasy that it is today.

Public Domain: From Menace to Sink Hole

Like Disney and Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, booksellers of Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries were victims of their own successes—and, left unchecked, would be the architects of their own demise.

The invention of the printing press increased literacy and access to books across the continent; which meant that it lowered the price of the printed word drastically as printers began reprinting their competitor‘s books as soon as they hit the shelves (and it also increased the cost of new works as printers kept seeking books to print that their competitors hadn‘t stolen).

The invention of the printing press increased literacy and access to books across the continent; which meant that it lowered the price of the printed word drastically as printers began reprinting their competitor‘s books as soon as they hit the shelves (and it also increased the cost of new works as printers kept seeking books to print that their competitors hadn‘t stolen).

What‘s more, dissent and criticism flowed freely, leading to social change. Poor people were learning from cheap books in a way that threatened to upend the class structure. Put together with the squeeze felt by publishers, unrestricted printing was deemed a “menace” by European governments; and central control and regulation began to fall into place. By the 18th century, copyright laws began to be passed and refined, stemming the tide.

However, that tide had produced “a people of poets and thinkers,” as literary critic Wolfgang Menzel called the German people of 1836, living under a post-printing but pre-copyright world. The free exchange of information, ideas, stories, and art has value to a nation; and so a middle ground was reached, wherein copyright protection would have an expiration date.

During its term, the author or their estate would control the work, receiving royalties from its production; and after the term expired, it would be available to the public. In the United States, the law is a bit complicated; but works created in 1928 and before (including Steamboat Willie) entered the public domain on January 1, 2024.

Works that are in the public domain are free to be reprinted and modified by anyone, at any time, without permission from or payment to its original creator—so, the way things were before copyright. This was criticized by academics like Alfred de Vigny, who maligned copyright expiration as a “fall into the sink hole of public domain.” But for creators like Walt Disney, it meant something much greater.

A Mouse in the Public Domain House

Because of copyright expiration, Walt Disney was free to include public domain music in his early animations—or to adapt public domain stories as feature-length animated films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Through the process, Disney used the characters, setting, themes, and events of the story, but adapted for the new medium in what was called a “derivative work.” While he and his company wouldn‘t own the rights to Snow White herself, or the events of her story, he could retain ownership over the specific animated version he had created.

Because of copyright expiration, Walt Disney was free to include public domain music in his early animations—or to adapt public domain stories as feature-length animated films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Through the process, Disney used the characters, setting, themes, and events of the story, but adapted for the new medium in what was called a “derivative work.” While he and his company wouldn‘t own the rights to Snow White herself, or the events of her story, he could retain ownership over the specific animated version he had created.

He could do so without consulting with anyone or getting approval from the original author (which would‘ve been tricky anyway, as the Brothers Grimm had died some seventy years prior). He didn‘t have to pay royalties on the story, also a boon for the fledgling (and financially fragile) company.

But perhaps most importantly to Disney, it meant that no one could come to him later and claim ownership over his work; he and his company would be able to maintain creative control until the copyright on his derivative work expired.

This bore dividends for the success of Disney‘s public domain adaptations, too: the grand, archetypal stories that the company chose to adapt were particularly primed to appeal to a broad audience. In short, that audience—we—love public domain stories.

Our Stories

That might seem like a bit of a strange idea, but it‘s well-attested; the high-minded idealism that demands “original stories” from Hollywood simply isn‘t a very profitable idea, historically. It‘s unexpected, though, to express love for public domain stories. What use could we have for an outdated, ninety-six year old story?

In part, this is survivorship bias: there are plenty of stories from 1928 that we don‘t have any interest in (who hasn‘t been waiting for King Stork of the Netherlands by Albert Lee, for instance?); and so the public domain stories that we‘re likely to notice losing copyright protection are the ones that have stuck around and remained relevant over time.

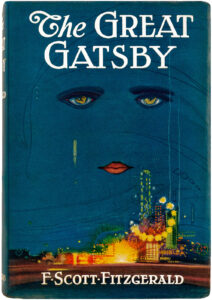

But that may also disguise the real reason: that the stories which do stick around are high quality, archetypal or even mythological in nature, and say something important or interesting to the people of the time. This doesn‘t just apply to the princess stories that made Disney a household name; but also to stories like that of Thor, appropriated by Marvel to be a superhero in 1962; or The Great Gatsby, the darling (and bane) of high school students across the country (itself a 2023 entrant into the public domain).

But that may also disguise the real reason: that the stories which do stick around are high quality, archetypal or even mythological in nature, and say something important or interesting to the people of the time. This doesn‘t just apply to the princess stories that made Disney a household name; but also to stories like that of Thor, appropriated by Marvel to be a superhero in 1962; or The Great Gatsby, the darling (and bane) of high school students across the country (itself a 2023 entrant into the public domain).

These are the stories we remember loving when we were kids, the ones we‘ll consider showing or reading to our children later in life; their big ideas and archetypal characters connect with us and feel worth passing down. Everything we create and enjoy has echoes of God‘s story; all the good ones, everything we remember after 96 years, rehearses creation somehow. Steamboat Willie itself might not have much to look back upon fondly, but Mickey‘s eventual reputation as an earnest, clever, resourceful, friendly underdog gives us a fond recollection of his character.

A Long-Awaited Freedom

But the hoopla about Mickey Mouse goes beyond just fond recollection or joy at finally having public ownership of such an iconic character. Most headlines about the character‘s freedom use the word “finally” or “at last;” and some articles even strike a doubtful tone, noting that the Disney Company is unlikely to simply “let the mouse go.” But it‘s not groundbreaking anymore, and in fact the rampant animal abuse in Steamboat Willie could be considered off-putting to people in 2024. So why the big party?

Part of this doubt has to do with the fact that no works lost copyright protection between 1998 and 2018, due to a 1998 law that extended copyright terms. For my entire adult life until 2018, for example, the process simply never happened. In many ways, the American people just aren‘t used to getting new public domain works, so distrusting this as a trick makes sense.

Still, copyright law is fairly unforgiving here. Despite some addenda, provisos, and quid-pro-quos, Steamboat Willie, Mickey Mouse, and Minnie Mouse—at least in their original forms—now belong to everyone. This tectonic shift has lit up the internet with posts, memes, and thinkpieces (including this one) since January 1; significantly brighter than we‘ve seen for previous Public Domain Days. In fact, the coverage of his changing status began last January, as the debate about whether or not Disney would try to lobby for another extension in 2023 began in earnest.

Still, copyright law is fairly unforgiving here. Despite some addenda, provisos, and quid-pro-quos, Steamboat Willie, Mickey Mouse, and Minnie Mouse—at least in their original forms—now belong to everyone. This tectonic shift has lit up the internet with posts, memes, and thinkpieces (including this one) since January 1; significantly brighter than we‘ve seen for previous Public Domain Days. In fact, the coverage of his changing status began last January, as the debate about whether or not Disney would try to lobby for another extension in 2023 began in earnest.

That tectonic shift, and the end of a long drama of political lobbying and legal wrangling, may in fact be a part of the reason for the sudden explosion in interest: we‘ve watched Disney fight hard to maintain control over Mickey Mouse, lest the squeaky-clean image they‘ve spent almost a century cultivating be sullied by a rude copyright violator. We‘ve seen them lobby Congress for an extension, working to get such a law passed for eight years before the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act was passed.

As a culture, we‘re also starting to become more educated about intellectual property now; and, largely due to Disney‘s lobbying from 1990-1998, the lapsed copyright of their most famous character (and likely the impetus for their crusade) feels like a little bit of a “finish line;” they can‘t, or at least don‘t have a compelling reason to, push back copyright terms again.

But, like Disney did 96 years ago, this could also steer the ship toward the beginning of derivative works; and indeed, mere moments after Mickey‘s entrance into the Public Domain, a trailer for a Mickey horror film (like the Winnie-the-Pooh movie from a few years ago) was released.

But, like Disney did 96 years ago, this could also steer the ship toward the beginning of derivative works; and indeed, mere moments after Mickey‘s entrance into the Public Domain, a trailer for a Mickey horror film (like the Winnie-the-Pooh movie from a few years ago) was released.

That film in particular probably isn‘t the next big thing. But somebody out there might just be the next Walt Disney, a visionary who just needs the right source material to make everything they ever wanted.

It‘s a long-awaited freedom, and seeing it happen to a kind and gentle fella is quite rewarding.

Public Domain: Recent Graduates

Steamboat Willie is far from the only 1928 work worth celebrating as it makes its way into public domain. If you‘re in the hunt for more public domain works, may we suggest:

Movies:

- The Thief of Bagdad, public domain since 2000

- Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last!

- Cecil B. DeMille’s first version of The Ten Commandments

- The first film adaptation of Peter Pan

- Don Juan the first film with synchronized audio (though it is music, not dialogue)

- Fritz Lang’s Metropolis

- The Jazz Singer, the first film to partially include synchronized dialogue, and its sequel The Singing Fool

- Cecil B. DeMille’s The King of Kings

- Oswald the Lucky Rabbit’s first adventure, Trolley Troubles

- Lights of New York, perhaps the first “all-talking” picture

- The Passion of Joan of Arc, considered by some film historians to be one of the greatest films ever made

Books

- About half of the Tarzan series, by Edgar Rice Burroughs

- Several Agatha Christie mysteries

- All of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries

- All of the Winnie-the-Pooh stories by A. A. Milne

- The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald

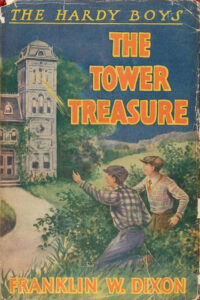

- The first few Hardy Boys books, in their pre-revision forms; the Stratemeyer Syndicate’s first really lasting hit series

- Millions of Cats, by Wanda Gág; the oldest American picture book still in print

…plus musical compositions, sound recordings, pieces of art, photographs, and more. For a more full list, check out Duke University’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain, and their Public Domain Day posts for 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, and (for context from the dark days) 2018.