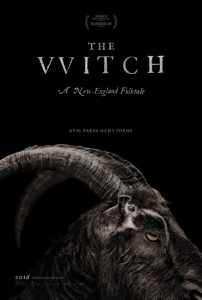

Review| The Witch

A few days back it was announced that Robert Eggers’ The Witch had gained public support from the Satanic Temple as “a Satanic experience.” I, in a potentially controversial move, publicly declared this news to be a good omen for the quality of the film. If an established substrate of Satanists found the movie to be something nuanced enough to represent their beliefs, then I figured the film might be more nuanced across the board, Satanists and colonial Puritan faith alike. Horror films set in a time near the infamous Salem witch trials tend to succumb to stereotypes and caricatures, mere straw men to be mocked and used for scares.

A few days back it was announced that Robert Eggers’ The Witch had gained public support from the Satanic Temple as “a Satanic experience.” I, in a potentially controversial move, publicly declared this news to be a good omen for the quality of the film. If an established substrate of Satanists found the movie to be something nuanced enough to represent their beliefs, then I figured the film might be more nuanced across the board, Satanists and colonial Puritan faith alike. Horror films set in a time near the infamous Salem witch trials tend to succumb to stereotypes and caricatures, mere straw men to be mocked and used for scares.

This, however, was not the case in The Witch. At the end of the film, there is a note that states how much of the narrative and dialogue came straight from actual primary sources such as court reports, diaries, etc. By the end of the film, one does feel like they were carried into a rather realistic depiction of the religious and social tensions weighing heavily on the landscape in those days. It is a credit to Robert Eggers—who wrote and directed—that he was confident enough in the source material to allow its inherent elements of suspicion and tension to speak for itself with little to no forced drama. The conclusion could include a supernatural or materialistic explanation and both would flow forth naturally from the ambiguity of the narrative.

While I do not claim to know the intricacies of the doctrines of the Satanic Temple, I can speak to a certain level of knowledge about the nature of Puritan forms of doctrine, teaching, and worship in colonial America. Maybe more than anything, I was surprised at how serious Eggers portrayed the faith of the central family, exiled into the wilderness from a colonial town. The family is loving towards each other (even with discipline and the annoyances of siblings rearing its head from time to time). Every member of the family is drawn with care and depth. The actors cast were utterly astounding in every role.

The father catechizes his children in the Christian faith and speaks nearly liturgical forms of prayers before meals (often matching those found in the Valley of Vision). The prayers and catechism questions are all rather true in style and content to what would have been found in Puritan writings of the day. When the family speaks of their faith and pray, their old English brings out the beauty of a deep and rounded Christian belief. It is refreshing to see this portrayal of a family with a strong and knowledgeable faith carried through the whole of the film. Not only do we have the draw of supernatural elements entering the reality of colonial America, but we have them entering into the reality of people that feel true to the time period with strong beliefs about the nature of the world and man.

Not everyone will appreciate this film. It is a slow burner with only the rare shock and really no jumps scares in its runtime. It is a film that wants to get under peoples’ skin for days instead of manufacturing momentary scares. It does the job quite well. The cinematography is beautiful and there are specific shots in the film that feel like paintings that were given life. It is the artistry of the film that requires it to be considered as superb film, not just an effective genre piece.

However, the most brilliant part of the film is just how layered with meaning it is. It has only been 14 hours since I walked out of the theater and I have  already found myself considering four or five different interpretations that could inform the meaning of the film. These readings range from the rather blunt (strong feminist undercurrents, man vs. nature) to more subtle readings. One such reading I found particularly interesting is how Eggers is able to speak in a very stark and profound way about the nature of America as a “Christian nation.” The film goes back to a period of American history that has always been considered to be the height of Christian affection in the country, whether Puritans, Quakers, other Separatists, etc., and throws that image in relief against the “post-Christian nation” we often refer to today.

already found myself considering four or five different interpretations that could inform the meaning of the film. These readings range from the rather blunt (strong feminist undercurrents, man vs. nature) to more subtle readings. One such reading I found particularly interesting is how Eggers is able to speak in a very stark and profound way about the nature of America as a “Christian nation.” The film goes back to a period of American history that has always been considered to be the height of Christian affection in the country, whether Puritans, Quakers, other Separatists, etc., and throws that image in relief against the “post-Christian nation” we often refer to today.

The ending suggests that the Christian faith of the family was ultimately not capable of overcoming its subversion by the black magic that resided out in nature, out in the woods around their land. The final moments of the film speak of the black magic as a means to “delicious living,” life of self-empowerment and little constraint on natural human desires, whatever they may be. In a sense, this conclusion speaks volumes to a country that finds more momentum in the self-help gurus of Oprah and Joel Osteen where we seek to empower ourselves toward a better life and in growing consumerism and commodification of just about everything as a way to attain our desires day to day. The “black magic” of our day has supplanted the deep religious affections that many of those who came to America from Britain in the early days of America maintained. Christian traditions and deeply rooted faith has been overcome.

The Witch is rather stark in its lack of resolution. It models its ambiguity and unwillingness to clearly show evil being completely defeated by good after the likes of Roman Polanski (Rosemary’s Baby, Repulsion) and William Friedkin (The Exorcist). However, these types of stories need to be told as well. Evil sometimes does overcome good in this world, even if only temporarily. However, when the credits rolled, I still had a sense that there was a standing hope in the frayed periphery of the story. With its reverent and rather accurately detailed account of strong, full faith within the life of a colonial family, it seems unlikely that this is the true ending of the story.

“It means,” said Aslan, “that though the Witch knew the Deep Magic, there is a magic deeper still which she did not know. Her knowledge goes back only to the dawn of time. But if she could have looked a little further back, into the stillness and the darkness before Time dawned, she would have read there a different incantation. She would have known that when a willing victim who had committed no treachery was killed in a traitor’s stead, the Table would crack and Death itself would start working backward.” – C.S. Lewis, The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, p. 163.

Great review. This is a fantastic way for Christians to approach films, even a film like this that I have absolutely no interest in seeing (not a fan of the genre). I was particularly jarred by this because I’d just read a review found in Movieguide that was written from such a completely different perspective.

https://www.movieguide.org/reviews/the-witch.html

Personally, I prefer the way Reel World Theology approaches movies.

Finally saw this myself. Man. “Superb” is an incredibly accurate descriptor. First film I’ve seen in 2016 that I just can’t shake…