Terraforming the Human Soul

Through Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry envisioned a future Earth with no war, disease, or division, a place of peace and human unity. It is an ideal that closely reflects the culmination of the Christian gospel, only without the Christian gospel. In Star Trek’s version, the gospel is that of humanity picking itself up by its own bootstraps and saving itself through the virtuous application of human genius and creativity.

Through Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry envisioned a future Earth with no war, disease, or division, a place of peace and human unity. It is an ideal that closely reflects the culmination of the Christian gospel, only without the Christian gospel. In Star Trek’s version, the gospel is that of humanity picking itself up by its own bootstraps and saving itself through the virtuous application of human genius and creativity.

The hopeful vision of humanity Roddenberry proposed was based, not in salvation through technology, but in the moral, spiritual, and social development of humankind. Star Trek’s most important future, then, is the future of the human heart. This is a future we can attain, it proposes, by embracing and holding fast to essential principles of freedom, equality, justice, exploration, and imagination. Whatever our technological development, it must never outpace our moral development. If it does, humanity is doomed.

One of the most potent interactions between technology and virtue in Star Trek is the technology of terraforming—the alteration of a dead planet’s atmospheric conditions in order to make it capable of supporting life. The idea is most famously and richly explored with the Genesis Device—the terraforming missile that provides the narrative through-line for the films Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. The Genesis Device narrative invites questions regarding the ethical use of technology and what statements Star Trek might be making—overtly or implicitly—about humankind’s preparedness for the use of such powerful technology

One of the most potent interactions between technology and virtue in Star Trek is the technology of terraforming—the alteration of a dead planet’s atmospheric conditions in order to make it capable of supporting life. The idea is most famously and richly explored with the Genesis Device—the terraforming missile that provides the narrative through-line for the films Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. The Genesis Device narrative invites questions regarding the ethical use of technology and what statements Star Trek might be making—overtly or implicitly—about humankind’s preparedness for the use of such powerful technology

The basic question of terraforming itself forces the hard question of technological hubris. How can humans possibly predict the effects of creating or re-shaping an entire world on the surrounding cosmos? McCoy powerfully raises such questions in conversation with Spock in Star Trek II when he learns of the enormous power of the Genesis Device. “According to myth,” he exclaims, “the Earth was created in six days. Now, watch out! Here comes Genesis. We’ll do it for you in six minutes!”

An even more stark statement comes in the Director’s Cut of the film when, at Spock’s “I do not dispute that in the wrong hands…,” McCoy interrupts, “’In the wrong hands?’ Would you mind telling me whose are the right hands, my logical friend?”

An even more stark statement comes in the Director’s Cut of the film when, at Spock’s “I do not dispute that in the wrong hands…,” McCoy interrupts, “’In the wrong hands?’ Would you mind telling me whose are the right hands, my logical friend?”

Here, McCoy suggests that there may be no right hands—no humans (or, presumably, aliens) who are morally and intellectually prepared to wield the power of God. It is this idea that intrigues science fiction novelist David Brin. “The Genesis Project,” he says, “can be looked upon as arrogant. It can be looked on as conceited. We are actually daring to try to pick up God’s tools and make a new form of life, a whole raft of new life forms in an ecology… This is the power of God. Is it a good thing that we’re trying to do it, or is it a bad thing?” (“Genesis & the Frankenstein Myth,” Star Trek III: The Search for Spock Collector’s Edition DVD, Special Features Disc)

But the creation of the Genesis Planet takes place in the shadow of the death of Spock. Indeed, as Kirk is making his way to the engine room when he realizes that Spock has sacrificed himself for the Enterprise crew, the film intercuts between Kirk’s descent into the bowels of the ship and the Genesis Planet forming. The hope of new life is springing forth in the context of Spock’s self-sacrificial death. In giving his life for his comrades, Spock has rescued them all from certain death at the hands of Khan and has specifically spared Kirk from Khan’s vengeance—a past mistake that came to cut him down when he was feeling old and tired. Spock has therefore given Kirk a new life. And, within its original context, it is clear that the focus of this scene is not on Genesis, as Spock, his sacrifice, and the freedom from death and emergence of new life it has produced are the undergirding theme here. Our characters are not just looking at a burgeoning new planet, but at the place toward which, presumably several minutes prior, Spock’s burial tube was launched. The creation of the Genesis Planet is not something anyone has intentionally undertaken. Rather, Khan used the Genesis device as a weapon, in an attempt to destroy Kirk and the Enterprise.  The emergence of a new planet is an unintended and unforeseen consequence of an intentionally destructive use of the Genesis device. This serves to carry on the film’s theme of life from lifelessness—or life from death—and hint at Spock’s return. McCoy’s question about humankind’s readiness for such technology has been overshadowed by the character story and left mostly unanswered. Of course, in the next film, that question will be explored in more detail..Haste and impatience are the primary factors tainting David Marcus’ design of the Genesis Device. But also at play are issues of using the right kind of technology, as David’s use of protomatter to speed the process and “solve certain problems” introduces instability into the Genesis matrix, thus adding new complications into the process. The entire question of terraforming cannot stand or fall on the fate of the Genesis Planet, as the technology used to create it was faulty. But the greater fault is in David. As David, Saavik, and the regenerating body of Spock are held hostage by Kruge’s crewmembers on the Genesis Planet, Kirk asks his son, “David, what went wrong?”

The emergence of a new planet is an unintended and unforeseen consequence of an intentionally destructive use of the Genesis device. This serves to carry on the film’s theme of life from lifelessness—or life from death—and hint at Spock’s return. McCoy’s question about humankind’s readiness for such technology has been overshadowed by the character story and left mostly unanswered. Of course, in the next film, that question will be explored in more detail..Haste and impatience are the primary factors tainting David Marcus’ design of the Genesis Device. But also at play are issues of using the right kind of technology, as David’s use of protomatter to speed the process and “solve certain problems” introduces instability into the Genesis matrix, thus adding new complications into the process. The entire question of terraforming cannot stand or fall on the fate of the Genesis Planet, as the technology used to create it was faulty. But the greater fault is in David. As David, Saavik, and the regenerating body of Spock are held hostage by Kruge’s crewmembers on the Genesis Planet, Kirk asks his son, “David, what went wrong?”

David replies, “I went wrong.” Again, the focus is not as much on the technology itself as it is on the moral condition of the humans using the technology.

David has failed morally. He has sinned. His ethical misstep has resulted in death and a fractured, dying creation that is collapsing in on itself under the weight of his shortcomings. In this moment, it is clear that the gravity of his actions—and the lives lost in pursuit of the technology he developed—have stayed with him. Then, at Kruge’s order, a Klingon officer produces a d’k tahg knife and stands behind Saavik, ready to strike.

In this moment, David chooses to change that narrative, to be a better version of himself. Spock’s regenerating body has no mind, no soul. David is the only one with the moral capacity to do something to save Saavik. David decides that no one else will die because of him. He chooses to sacrifice himself, attacking the Klingon, who ultimately guts him. This is David’s act of nobility, of moral fortitude that offers him some redemption against the destruction for which he is responsible.

In this moment, David chooses to change that narrative, to be a better version of himself. Spock’s regenerating body has no mind, no soul. David is the only one with the moral capacity to do something to save Saavik. David decides that no one else will die because of him. He chooses to sacrifice himself, attacking the Klingon, who ultimately guts him. This is David’s act of nobility, of moral fortitude that offers him some redemption against the destruction for which he is responsible.

“He gave his life to save us,” Saavik says. These words could just as easily be about Spock in the previous film. These films are about the unfolding of the resonant effects of Spock’s sacrifice, and self-sacrifice is a recurring theme. If David had been unrepentant, if he had hardened his heart and tried to deny that the Genesis Planet was falling apart, railing against the idea that he had failed, and the planet had swallowed him up in response, David’s death would have been judgment and defeat. What happens, though, is that David admits his guilt to himself, to Saavik, and to his father. The planet is only behaving according to what David has put into it of himself. David’s brokenness has become the brokenness of Genesis. He confesses it and chooses to do something to keep the innocent from dying. He chooses to stand up and do what is right. Here, he transitions from a villain to a hero, when he “atones” for his own mistakes by accepting death in Saavik’s place.

Star Trek has a dual narrative: Humans are amazing. We have advanced greatly. We have things to be proud of. We will improve and we can improve ourselves. But, we are a tiny speck in the universe. We must have the humility to realize that we are not “there” yet. There is still brokenness in our hearts. There are still challenges against which we are powerless. The task before us is not simply about using technology for good vs. using it for evil. It’s about having a good moral compass and a disciplined approach so that we can avoid mistakes along the way, even toward an ostensibly noble goal. The problem for David is that he stops worrying how he will get there. When our methods become subordinated to our goals, we show the true nature of our moral readiness for any power or responsibility with which we may be entrusted.

The Genesis Device raises the question: Is terraforming an example (albeit fictional) of human pride reaching beyond the realm in which humans are meant to operate? Or is it humanity following the next logical step in its use of the ingenuity given to it by God and fulfilling its role as cultivators of Creation? Additionally, the speed at which the Genesis Device delivers the desired effect—forming a planet in what appears to be minutes when it is detonated inside a nebula—poses particular problems that may only ever exist in pure conjecture. But does taking time to perform the task of terraforming carefully and in stages, represent a more morally praiseworthy approach to the act of terraforming? Star Trek would seem to say so.

The Genesis Device raises the question: Is terraforming an example (albeit fictional) of human pride reaching beyond the realm in which humans are meant to operate? Or is it humanity following the next logical step in its use of the ingenuity given to it by God and fulfilling its role as cultivators of Creation? Additionally, the speed at which the Genesis Device delivers the desired effect—forming a planet in what appears to be minutes when it is detonated inside a nebula—poses particular problems that may only ever exist in pure conjecture. But does taking time to perform the task of terraforming carefully and in stages, represent a more morally praiseworthy approach to the act of terraforming? Star Trek would seem to say so.

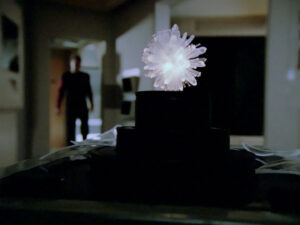

By the 24th century, terraforming is a common enough practice to be casually mentioned on a few times in episodes of The Next Generation and Deep Space Nine, but rare enough to still be somewhat unfamiliar to active Starfleet officers. In the Next Generation episode “Home Soil,” we see Star Trek’s most in-depth discussion of the moral implications involved in terraforming since Star Trek II and III. In the episode, the Enterprise pays a visit to Telara III, where a terraforming operation is underway. Upon their arrival in orbit, they meet with a strangely uncooperative attitude from the project’s leader, Director Kurt Mandl, who does not want them to beam down. Suspicious, Picard sends an away team anyway and soon a perfectly normal tour gives way to some more odd occurrences, culminating in the apparent murder of one of the terraformers.

The episode covers terraforming with reference to both ethics and (by some extension) the Genesis Device from several directions. First, it recalls the Genesis Device by connecting terraforming with Biblical imagery. When the away team first arrives at the terraforming station, they are greeted by a scientist named Luisa Kim, who introduces herself as “Gardener of Edens” and admits that “Terraforming makes you feel a little godlike.” This recalls David Brin’s description of terraforming as “picking up God’s tools,” as well as Kirk, Spock, and McCoy’s discussion of the implications inherent in the power of creation.

The episode covers terraforming with reference to both ethics and (by some extension) the Genesis Device from several directions. First, it recalls the Genesis Device by connecting terraforming with Biblical imagery. When the away team first arrives at the terraforming station, they are greeted by a scientist named Luisa Kim, who introduces herself as “Gardener of Edens” and admits that “Terraforming makes you feel a little godlike.” This recalls David Brin’s description of terraforming as “picking up God’s tools,” as well as Kirk, Spock, and McCoy’s discussion of the implications inherent in the power of creation.

Secondly, while both the process undertaken on Velara III and Genesis effect bring “life from lifelessness” and occur in stages, their stages are quite different. Carol Marcus explains Genesis in her proposal video.

The device is delivered, instantaneously causing what we call the Genesis Effect. Matter is reorganized with life-generating results. Instead of a dead moon, a living, breathing planet, capable of sustaining whatever life forms we see fit to deposit on it.

In Marcus’ proposal, there are many similarities with Kim’s description of terraforming in “Home Soil.” However, there are striking differences. Kim describes the process on Velara III this way.

What we’re doing is so exciting, so inspiring. We take a lifeless planet and little by little transform it into an M-class environment, capable of supporting life… when the process is complete eventually, we’ll have a lush, arable biosphere.

According to the display on Kim’s computer, this process takes 30 to 35 years, highlighting the central difference between Mandl’s operation and the Genesis Device. The process used in the 24th century is remarkably slower and more careful than the near-instantaneous Genesis effect, representing, in a certain sense, a major technological step backward. Presumably, once the failure of the Genesis Planet brought the instability of the Genesis matrix to light, scientists had to find new ways to terraform planets that did not indulge in the same cutting of corners facilitated by David Marcus’ use of protomatter.

According to the display on Kim’s computer, this process takes 30 to 35 years, highlighting the central difference between Mandl’s operation and the Genesis Device. The process used in the 24th century is remarkably slower and more careful than the near-instantaneous Genesis effect, representing, in a certain sense, a major technological step backward. Presumably, once the failure of the Genesis Planet brought the instability of the Genesis matrix to light, scientists had to find new ways to terraform planets that did not indulge in the same cutting of corners facilitated by David Marcus’ use of protomatter.

But one ethical consideration remains constant between both processes: The planet chosen must be lifeless. “You boys have to be clear on this,” Carol says to Chekov and Captain Terrell, “There can’t be so much as a microbe or the show’s off.” The implication here is that the terraformers are thinking long-term. They do not want to obliterate any life that may have the chance to evolve into higher life forms on its own if allowed to develop naturally. Indeed, in Kim’s presentation of Mandl’s process, she explains, “The planet must also be without life or the prospect of life developing naturally.” This is the very problem into which Mandl has run, as it is revealed that the scientist who died was killed by microscopic life forms who, in a bid to save their species from obliteration, infiltrated the computer controlling the laser he was using, turning it into a deadly weapon. Mandl is aware of the evidence that these life forms exist, but as they are not carbon-based and therefore do not fit any previously known definition of life, he has dismissed the possibility that they are alive. He emphasizes to Picard that he and his team “were assured, not once but many times, by the best scientific minds in the Federation, that this planet has no life. No life! And we were not looking, and therefore we did not see.”

Like David, Mandl is obsessed with his work. According to Troi, this is not uncommon. Obsessive behavior, she says, “frequently goes with the career profile” of terraformers. Before the microscopic life forms are discovered, Picard suggests that Mandl’s obsession may have driven him to kill a scientist who he might have perceived as standing in his way. What we see, though, is that Mandl has no desire to kill. “I create life!” he insists, “I don’t take it!” Still, however, his drive to complete the terraforming project did cause him to be blind to—or to explain away—evidence that a more objective perspective (the Enterprise computer) correctly identifies as signs of life. In this sense, his obsession does very nearly drive him to potentially kill countless entities, however passionately he may have convinced himself this was not the case.

Like David, Mandl is obsessed with his work. According to Troi, this is not uncommon. Obsessive behavior, she says, “frequently goes with the career profile” of terraformers. Before the microscopic life forms are discovered, Picard suggests that Mandl’s obsession may have driven him to kill a scientist who he might have perceived as standing in his way. What we see, though, is that Mandl has no desire to kill. “I create life!” he insists, “I don’t take it!” Still, however, his drive to complete the terraforming project did cause him to be blind to—or to explain away—evidence that a more objective perspective (the Enterprise computer) correctly identifies as signs of life. In this sense, his obsession does very nearly drive him to potentially kill countless entities, however passionately he may have convinced himself this was not the case.

In “Home Soil,” where terraforming is referred to as making one feel “godlike” and like a “Gardener of Edens,” we see that humans are not God, that there was life present before the terraforming team arrived and they do not have the right to wipe it out—even though they have the power to do so. The story also shows us that a “god” must respect even the smallest life form, including life forms that are so fundamentally different as to be almost unrecognizable as life. No matter how different we are from God, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant we are in comparison, God has compassion on us.

But human beings are gardeners of Eden. Our initial calling, according to the Biblical narrative, was indeed to be gardeners. And, as our creativity and ingenuity show, we are still cultivators of Creation. Star Trek recognizes this responsibility within the Genesis Device story. In Star Trek IV, Earth is on the precipice of destruction because human beings were not good caretakers. They hunted humpback whales to extinction and brought about their own doom. Only through undoing the effects of their sin can their destruction be averted, as Spock, Kirk, and the Enterprise crew not only save humanity, but restore order to the planet. We may never have an alien probe scouring our planet for communication from whales, unintentionally destroying our planet in the process, and we are unlikely to be shaping or creating worlds any time soon, but the clear message in Star Trek is that our technological advancement must never outstrip our moral fortitude.

But human beings are gardeners of Eden. Our initial calling, according to the Biblical narrative, was indeed to be gardeners. And, as our creativity and ingenuity show, we are still cultivators of Creation. Star Trek recognizes this responsibility within the Genesis Device story. In Star Trek IV, Earth is on the precipice of destruction because human beings were not good caretakers. They hunted humpback whales to extinction and brought about their own doom. Only through undoing the effects of their sin can their destruction be averted, as Spock, Kirk, and the Enterprise crew not only save humanity, but restore order to the planet. We may never have an alien probe scouring our planet for communication from whales, unintentionally destroying our planet in the process, and we are unlikely to be shaping or creating worlds any time soon, but the clear message in Star Trek is that our technological advancement must never outstrip our moral fortitude.

David Marcus’ methods ultimately represent a use of technology as a substitute for virtue. In Star Trek, this kind of shortcutting always leads to disaster. Whether it’s the M-5 computer trying to run a starship without human judgment and instinct, an overzealous engineer whose plan to increase starship warp capability is powered as much by hubris as untested methodology, or a Starfleet doctor whose rush to be a planet’s savior leads him to develop a cure that kills,* impatient science is a quick way to commit perhaps Star Trek’s cardinal sin—playing God. In Star Trek, the amazing power of human ingenuity must always be tempered with humility and moral grounding, often resulting in less spectacular, but more sustainable results. We should be spurred on, then, by imagining the possibilities, but wise enough to realize that the kind of patience and care required in order to bring about those possibilities may mean we never see them realized in our lifetimes. In an age of blindingly fast scientific advancement—frequently based on realizing ideas imagined by Star Trek—we would do well to listen to the lessons of the Trek universe, which tell us, along with the Apostle Paul, to carry out our endeavors “with all humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another in love.”