Peanuts, Franklin, and Sincere Diversity

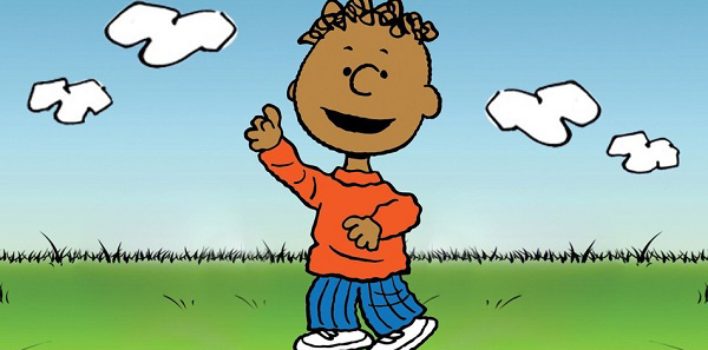

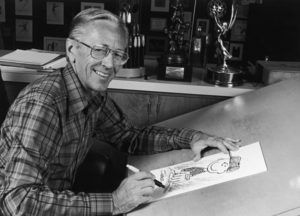

Fifty years ago, Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz introduced the character Franklin into his now-iconic comic strip. This was a significant moment in Peanuts history, as the strip had never had a black character before. Since that first appearance, Franklin became a regular member of Charlie Brown’s circle of friends – an acute and hilarious observer of the rest of the gang’s many foibles and idiosyncrasies, while also having some of his own.

The story of just how Franklin became a part of Peanuts is really amazing in its own humble way. Like the Peanuts strip itself, it’s a story that is simple but so profound. And we today can learn a lot from how Charles Schulz integrated the character into the cast.

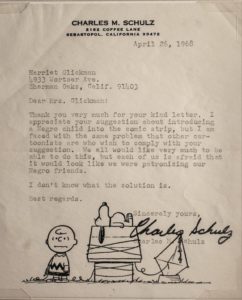

It began with a letter from a schoolteacher in California. In the wake of the tragic assassination of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in April of 1968, Harriet Glickman wrote to Charles Schulz and suggested that integrating a black character into the Peanuts strip would be helpful in healing the country and establishing good race relations.

It began with a letter from a schoolteacher in California. In the wake of the tragic assassination of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in April of 1968, Harriet Glickman wrote to Charles Schulz and suggested that integrating a black character into the Peanuts strip would be helpful in healing the country and establishing good race relations.

In his reply, Schulz thanked Mrs. Glickman for her suggestion, but admitted that he was apprehensive about the idea. But not because he was fearful of the consequences or that he was a racist himself – far from it, in fact. Schulz didn’t want to seem patronizing or condescending to his black readers.

In other words, Schulz respected all his readers, whatever their color, and didn’t want to be inauthentic or insincere in his creativity in order to pander to a specific demographic. Charles Schulz derived the humor of his strip from the authentic emotions found within himself. His readers sympathized with, and subsequently laughed at, Charlie Brown and his friends because they understood Schulz’s characters’ emotional underpinnings, which were universal ones experienced by the whole of humanity.

Over the next few months, Glickman and Schulz corresponded, with the former trying to convince the latter that Peanuts was one of the best ways to help mend the divide between races. After many letters, and I’m sure a lot of thought on Schulz’s part, he informed Glickman that he was going to attempt to introduce a black character, but only if he could do it in his own way – with simple sincerity.

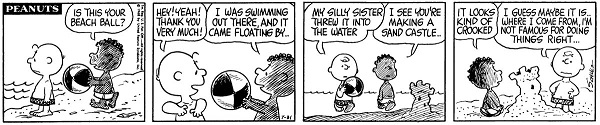

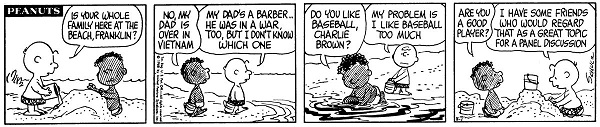

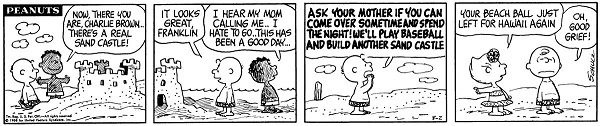

Franklin’s first appearance came in the July 31, 1968 daily Peanuts strip. It was a simple four-panel gag. Charlie Brown and Franklin meet on the beach (it was summertime, after all), with Franklin finding Charlie Brown’s lost beach ball. Over the next three strips, Schulz expanded the story. Charlie Brown and Franklin have a simple conversation while doing a fun activity (building a sand castle) before parting ways.

What Schulz did in these strips was extremely profound, and definitely in line with his emotional sincerity and gentle genius. Schulz opened the eyes of the American public to a way of thinking about race that was right in line with the teachings of Dr. King – and created one of the best tributes to the slain civil rights leader that has ever been done.

In that first set of strips, Franklin was just another kid in the Peanuts universe. His race wasn’t given a thought or brought up by either him or Charlie Brown. They bonded over things they had in common – their fathers fought (or were fighting) in wars overseas and they both liked baseball. And finally, they both worked together to build a proper sand castle.

Charles Schulz helped race relations by not calling attention to it and making interactions between people of different colors as regular and mundane as any conversation. He also showed that people of all colors can put their minds and talents together and build something.

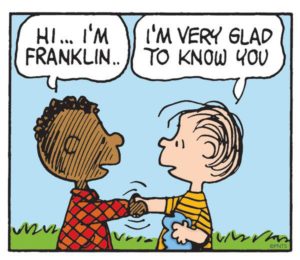

Even the design of Franklin is insightful in its simplicity and draws from Schulz’s sincerity (if you’ll excuse the pun). He looks, more or less, exactly like Charlie Brown – just with darker skin and an actual tuft of hair on his head. In his own creative way, Schulz was saying that there really isn’t any difference between people of different skin pigmentations. We’re all just people, period.

In terms of blowback at the time, Schulz said that he received a letter from a newspaper editor in the South. “[He] said something about, ‘I don’t mind you having a black character, but please don’t show them in school together,’ Because I had shown Franklin sitting in front of Peppermint Patty,” Schulz recalled in a 2000 interview with author Thomas Inge. “But I didn’t even answer him.”

In his most famous speech, Dr. King said that he hoped that his “four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” And that’s what Charlie Brown’s first encounter with Franklin emulated. Franklin wasn’t a token black character, but a real person. He and Charlie Brown bonded over shared interests and ideas. Charlie Brown gravitated toward Franklin because Franklin was a good person.

Schulz’s subtle and sincere approach is a far cry from today. If this were done in today’s “woke,” unsubtle, insincere, lazy, virtue-signaling, diversity-mongering culture that constantly condescends to people of color, there would be great fanfare that accompanied the strip’s first printing. And it would seem that the introduction of Franklin would be more about making people who see themselves as great civil rights champions feel better about themselves than about actual race relations.

Schulz’s subtle and sincere approach is a far cry from today. If this were done in today’s “woke,” unsubtle, insincere, lazy, virtue-signaling, diversity-mongering culture that constantly condescends to people of color, there would be great fanfare that accompanied the strip’s first printing. And it would seem that the introduction of Franklin would be more about making people who see themselves as great civil rights champions feel better about themselves than about actual race relations.

“Be careful not to practice your righteousness in front of others to be seen by them. If you do, you will have no reward from your Father in heaven.” Matthew 6:1

In the sixth chapter of Matthew, Jesus began His teaching by emphasizing that it is better to do good things in secret than with the “trumpets” of accolade and adulation. Righteous deeds should be accompanied by a heaping helping of humility. The same principle can be applied to Charles Schulz and his introduction of Franklin. The character was a quiet and subtle nudge in the right direction (normalizing interactions) – not a smug, snarky and prideful slap.

It’s absolutely condescending, counterproductive, stupid, and, most importantly, unbiblical to constantly point out the differences in people to make ourselves feel like great crusaders for civil rights. The truth is the lazy, intellectually dishonest race-mongers of today can’t hold a candle to the actual civil rights activists of over half a century ago. Attacked by real institutional racism, these brave men and women did the heavy lifting that has elevated and deepened us. Today, we’re simply standing on the shoulders of giants – people now perceive institutional racism where it no longer exists.

It’s absolutely condescending, counterproductive, stupid, and, most importantly, unbiblical to constantly point out the differences in people to make ourselves feel like great crusaders for civil rights. The truth is the lazy, intellectually dishonest race-mongers of today can’t hold a candle to the actual civil rights activists of over half a century ago. Attacked by real institutional racism, these brave men and women did the heavy lifting that has elevated and deepened us. Today, we’re simply standing on the shoulders of giants – people now perceive institutional racism where it no longer exists.

“This righteousness is given through faith in Jesus Christ to all who believe. There is no difference between Jew and Gentile, for all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God.” Romans 3:22-23

If we are truly going to get past the actual racism of the past, there must be genuine forgiveness in the hearts of ALL people (white, black, or whatever) courtesy of the Holy Spirit and the forgiveness of our own sins through Jesus Christ, followed by a genuine letting go of past racism. If we are to move forward, the ability to call back and compare past institutional racism to what goes on today (as if there is any comparison) has to stop.

In a 2005 interview with Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes, actor Morgan Freeman spoke about this problem in a simple yet profound way. When asked by Wallace how we, as a society, are going to get rid of racism, Freeman curtly responded, “Stop talking about it.”

Wallace was initially stunned a bit by the frankness of Freeman’s response. “I’m going to stop calling you a white man, and I’m going to ask you to stop calling me a black man,” Freeman elaborated. “I know you as Mike Wallace. You know me as Morgan Freeman.” I loved this exchange because Freeman bluntly points out how simple it is to treat people like people – just like Charles Schulz did with his comic strip.

Constantly pointing out racial differences in people was not helping the cause of race relations. We are all individuals – fashioned by a God who loves every one of us equally. Therefore, we are equally susceptible to sin and are all equally in need of forgiveness by our Creator through Jesus Christ.

As long as there is sin in the world, there will always be a semblance of racism and prejudice. People – ALL people – are sinful by nature. No color of people is more or less virtuous in the eyes of God (whose judgment is the only one that truly counts) because of something as superficial as the amount of melanin in one’s skin. Black pride, white pride, brown pride – it’s all the same and one is just as toxic and sinful as the other. Skin color is such a stupid thing to be hung up about – and that goes for people of ALL colors.

Our culture does not need the selfish, inauthentic, virtue-signaling pomp of those who pride themselves on how many black friends they have. We need the subtle, beautiful, and biblical sincerity of normal, everyday interactions between real people – as emphasized by Charles Schulz’s brilliant but simple first conversation between Franklin and Charlie Brown five decades ago. That’s the real legacy of Dr. King at work, and it is the only way we will all learn to see each other as fellow children of God and nothing more.

“There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Galatians 3:28