Reviewing the Classics| The Gospel According to St. Matthew

When Pier Paolo Pasolini, the Italian director of The Gospel According to St. Matthew, was asked why his movies so often dealt with religious themes despite his communist leanings and professed atheism, he responded, “If you know that I am an unbeliever, then you know me better than I do myself. I may be an unbeliever, but I am an unbeliever who has a nostalgia for a belief.” The first inclination of a believer may be to scoff at Pasolini’s languid assessment of his own spirituality, but his sentiment can and should give the Christian believer pause when reflecting on the director’s 1964 film. It illuminates Pasolini’s own interests and ambitions with a dramatization of Matthew’s gospel and also brings into relief how a Christian may cultivate greater faith from the artistic works of those who do not share the same religious convictions.

When Pier Paolo Pasolini, the Italian director of The Gospel According to St. Matthew, was asked why his movies so often dealt with religious themes despite his communist leanings and professed atheism, he responded, “If you know that I am an unbeliever, then you know me better than I do myself. I may be an unbeliever, but I am an unbeliever who has a nostalgia for a belief.” The first inclination of a believer may be to scoff at Pasolini’s languid assessment of his own spirituality, but his sentiment can and should give the Christian believer pause when reflecting on the director’s 1964 film. It illuminates Pasolini’s own interests and ambitions with a dramatization of Matthew’s gospel and also brings into relief how a Christian may cultivate greater faith from the artistic works of those who do not share the same religious convictions.

Born from inspiration after reading through the four gospels in his hotel room while attending a papal-hosted seminar in the Italian city of Assisi, Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew is a dramatic rendition of the story of Jesus from the opening chapter of the Nativity through the Resurrection. While not a word-for-word narrative–his film contained no screenplay–it draws dialogue and dramatic direction straight from Matthew’s gospel. His contention for the choice was the images put forth on the screen could never aspire to the same “poetic heights” as the words found in the Bible. A fitting rationale given his first forays into the arts was poetry and his life-long identification as primarily a poet.

This self-identification manifests itself immediately in the opening sequence of the film. Mary and Joseph are introduced with little to no dialogue but for the angel’s words to Joseph assuring him of Mary’s immaculate conception. Mood and tension, especially the unspoken tension of Joseph’s intention to divorce Mary, is beautifully communicated through close up shots of the actor’s faces. Mary, in particular, is framed as if out of a renaissance era painting to communicate a breadth of emotional depth from silent sorrow to joyful worship of transpiring events. This odic approach to the opening moments is a microcosm of the film using quiet images to loudly proclaim the holy gravity of Matthew’s gospel and verges with Pasolini’s common life declaration of, “all is sacred.”

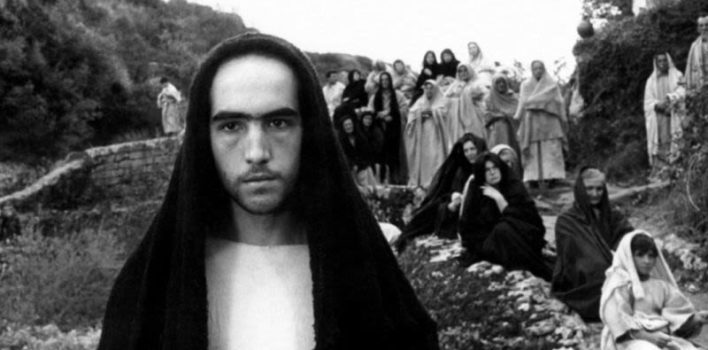

It’s slightly dissonant, given the reverential tone of the material, the Jesus presented in the film. Played by Enrique Irazoqui, a local economics student Pasolini had met shortly before filming, Jesus is the son of God: healing a leper, walking on water, and multiplying the loaves and fish. However, all of these scenes lack ceremony and are done in such a way to communicate a reluctance on Jesus’ part to perform them at all. It is here in these moments Pasolini’s Marxist-motivated atheism is most apparent. He went so far after the premiere of the film to say of the inclusion of the miracles “ashamed” him and were “disgusting Pietism.” Likewise, the matter-of-fact treatment of Jesus’ death and resurrection speak further to the lack of attention given to Jesus’ divine mission as the Son of God.

Such a severe distaste for the miracles of Jesus would seemingly make the movie a lifeless, contrarian take on the gospel narrative. However, the film remains vibrantly compelling because of Pasolini’s strong focus on the words of Jesus. His Jesus is a people’s Jesus. An iconoclast rigidly positioned for the poor, oppressed, and marginalized and opposed to the powerful religious elite benefitting and exploiting the downtrodden for their own gain. At multiple points throughout the film, Jesus speaks like a revolutionary firebrand, hurling the Scriptures and his authority at the Pharisees as the crowds listen intently. There is one great moment where Jesus is surrounded by children, a common group looked on with low regard, as he fields the potentially ensnaring questions of the Pharisees in the Temple. When he responds to their sophistry with particularly biting aplomb, the group of on-looking children turns back to the religious leaders with wry, content grins on their faces.

And yet, in spite of the downplaying of Jesus’ religious significance as the Christ and spiritual significance as the Son of God, Pasolini’s movie is captivating for any Christian because of the magnetism of Jesus’ words. It is easy to forget because of two thousand years of church history how radically compelling his teachings were. One particular sequence is the Sermon on the Mount. Covering multiple chapters in Matthew’s gospel, it takes up only a few minutes in the movie, but it is one of the more powerful moments in the entire two-plus hour runtime. The whole sequence is shot in close-ups of Jesus’ face as he pronounces the Beatitudes, loving your enemies, and being a light in the world. It culminates in a nighttime thunderstorm–we often forget the Sermon on the Mount lasted a long time–with Jesus professing the Lord’s Prayer. While it might not have been the intention of Pasolini, the moment thunders with both Jesus’ authority and the Lord’s prayer reminds us of his sustaining power even as the storms of life rage around us.

Ultimately, the movie’s simple focus on the words of Jesus and lack of dramatic adornment is both what it lacks and what is most compelling for audiences and those interested in the life of Christ. Pasolini set out to create a narrative from the perspective of those who followed Jesus. The cinema verite style of the film, especially during Jesus’ trial where it almost feels like the filmmaker was on hand for the actual events, cinematically illustrate the broad appeal of Jesus’ teachings. While an atheist or Marxist might be drawn to Jesus’ strong words against elites, a spiritual seeker will be drawn to the divine authority in his words. A lowly, poor person will be captivated by his message of deliverance, while a broken man will find healing and strength. Pasolini did not set out to create a film evangelizing the masses, yet he did create a classic piece of art prompting Christians and non-Christians alike to contemplate the words of Jesus Christ.